It has been a really long time since I did new reviews of Nepali or Tibetan-style Indian incenses. In the current era I don’t know if there is one dominant shopping point for these types of incenses like there was when Essence of the Ages was active, although Hither & Yon in Hawaii is a good source for lines like Dhoop Factory and you can usually find a lot of the more common Nepali incenses through places like Incense Warehouse. The problem, which is something I don’t think you find in actual Tibetan incenses, is there are a lot of poor Nepali incenses. When I explored them back in the 00s I ended up getting rid of a great deal of them because they were basically just unpleasant and cheap woody incenses without much in the way of aroma. The worst felt like bad perfumes on junk sawdust. But of course this isn’t true of all of them (several of the Dhoop Factory incenses are upper echelon Tibetan-style incenses in my book). Nowadays there are a number of smaller shops on the internet and across Etsy that actually show there are multiple traditions (or maybe exporters) of these sorts of incenses. I even dug up what appears to be a rather interesting line of perfumed Tibetan-style incenses sources in India. So I got busy and have ordered quite a few Nepali incenses, just mostly going on intuition to pick things out. Along the way I’ve also rediscovered sources for things I reviewed way back and will update those accordingly. The first two here are incenses handmade in Nepal for California’s Chagdud Gonpa Foundation. Both of these can be found at the Tibetan Treasures online shop.

It has been a really long time since I did new reviews of Nepali or Tibetan-style Indian incenses. In the current era I don’t know if there is one dominant shopping point for these types of incenses like there was when Essence of the Ages was active, although Hither & Yon in Hawaii is a good source for lines like Dhoop Factory and you can usually find a lot of the more common Nepali incenses through places like Incense Warehouse. The problem, which is something I don’t think you find in actual Tibetan incenses, is there are a lot of poor Nepali incenses. When I explored them back in the 00s I ended up getting rid of a great deal of them because they were basically just unpleasant and cheap woody incenses without much in the way of aroma. The worst felt like bad perfumes on junk sawdust. But of course this isn’t true of all of them (several of the Dhoop Factory incenses are upper echelon Tibetan-style incenses in my book). Nowadays there are a number of smaller shops on the internet and across Etsy that actually show there are multiple traditions (or maybe exporters) of these sorts of incenses. I even dug up what appears to be a rather interesting line of perfumed Tibetan-style incenses sources in India. So I got busy and have ordered quite a few Nepali incenses, just mostly going on intuition to pick things out. Along the way I’ve also rediscovered sources for things I reviewed way back and will update those accordingly. The first two here are incenses handmade in Nepal for California’s Chagdud Gonpa Foundation. Both of these can be found at the Tibetan Treasures online shop.

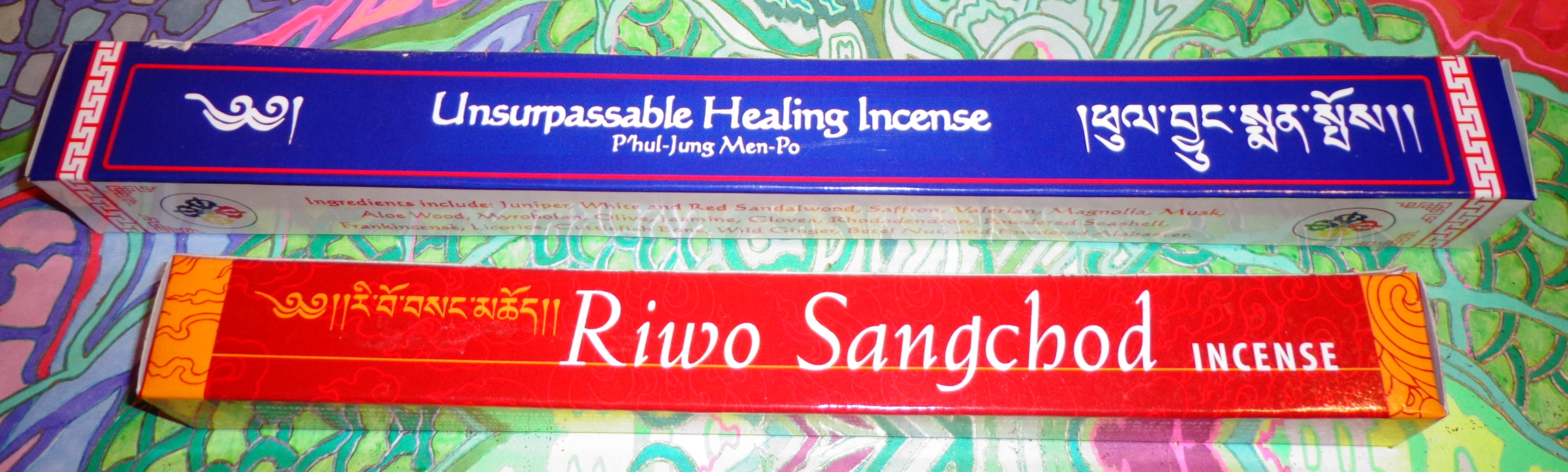

Riwo Sangchod reminds me most of the Tashi Lhunpo Shing Kham Kun Khyab red stick I reviewed almost 16 years ago, although since it’s been that long I would imagine this one isn’t quite as deluxe. It’s possibly the Nepali equivalent of a Bhutani red stick (there are two Riwo Sangchod incenses from Bhutan in the Tibetan Treasures catalog as well) but obviously having a completely different scent profile. It has an impressive list of more than ninety ingredients, including sandalwood, betel nut, aloeswood, juniper, musk, frankincense, wormwood, cedar, rhododendron, spikenard, wild ginger, magnolia, valerian, myrobalan, seashell, jasmine, cloves, cardamom, saffron, olive, licorice, gold, silver, turquoise, amber, and silk brocade. And as you can imagine, with such an impressive list of ingredients (I think this is my first with turquoise or silk brocade!), everything has been blended down to a completely composite aroma, one that is friendly and sweet on top while still having quite a bit of complexity swirling around beneath. Like in Bhutanese incenses, this has characteristics I’d describe as woody and berry-like all at once, it’s clearly not a Tibetan secret to pair these aspects together as they’re always a really friendly match. This isn’t a spectacular incense, I wouldn’t even call any of the Bhutanese equivalents spectacular either, but what they are is light and really accessible. And at least in this case the ingredients feel up to snuff and not at all watered down. Several sticks of this more or less confirmed my static opinion of this one, but keep in mind what I said about the complexity, some of the subscents churn underneath and show up in different temperatures so this one isn’t being phoned in. The subtle woodiness is quite nice here.

Riwo Sangchod reminds me most of the Tashi Lhunpo Shing Kham Kun Khyab red stick I reviewed almost 16 years ago, although since it’s been that long I would imagine this one isn’t quite as deluxe. It’s possibly the Nepali equivalent of a Bhutani red stick (there are two Riwo Sangchod incenses from Bhutan in the Tibetan Treasures catalog as well) but obviously having a completely different scent profile. It has an impressive list of more than ninety ingredients, including sandalwood, betel nut, aloeswood, juniper, musk, frankincense, wormwood, cedar, rhododendron, spikenard, wild ginger, magnolia, valerian, myrobalan, seashell, jasmine, cloves, cardamom, saffron, olive, licorice, gold, silver, turquoise, amber, and silk brocade. And as you can imagine, with such an impressive list of ingredients (I think this is my first with turquoise or silk brocade!), everything has been blended down to a completely composite aroma, one that is friendly and sweet on top while still having quite a bit of complexity swirling around beneath. Like in Bhutanese incenses, this has characteristics I’d describe as woody and berry-like all at once, it’s clearly not a Tibetan secret to pair these aspects together as they’re always a really friendly match. This isn’t a spectacular incense, I wouldn’t even call any of the Bhutanese equivalents spectacular either, but what they are is light and really accessible. And at least in this case the ingredients feel up to snuff and not at all watered down. Several sticks of this more or less confirmed my static opinion of this one, but keep in mind what I said about the complexity, some of the subscents churn underneath and show up in different temperatures so this one isn’t being phoned in. The subtle woodiness is quite nice here.

Perhaps even more impressive than the Riwo Sangchod is Chagdud Gonpa Foundations’s Unsurpassable Healing Incense, one of the few Nepali incenses that actually approaches the level of some of the better Tibetan incenses. Thanks to the categories here I found that this was also in Anne’s Top 10 in 2011! It has a similar ingredient profile to the Riwo Sangchod, with juniper, white and red sandalwood, saffron, valerian, magnolia, musk, aloeswood, myrobalan, olive, jasmine, clove, rhododendron, powdered seashell, frankincense, licorice, cuttlefish bone, wild ginger, betel nut, and powdered alabaster, but even though there are some similarities to the berry/woody mix of that incense, the ingredients add up to something a lot more complex. The first thing I get is some top layer of peppery spice. Second the middle with the woods and saffron. There’s definitely some musk in the mix which is almost entirely absent or at least not noticeably present in most Nepali incenses. As the smoke spreads out more of the incense’s floral notes come out a bit more as well as what seems like a bit of an agarwood note. It only remains noticeably Nepalese by the base which, despite all the other ingredients, still seems a bit (too?) high in juniper or some other cheap sawdust content. Also present are some of the notes found in the Riwo Sangchod as if the incense fractalizes at times. Ultimately there is really a lot going on this one and it can be intensely fascinating to realize that it might take some time to see it at as recognizable rather than ever-changing. In fact I really liked Anne’s description of this as an “all rounder,” it’s almost the perfect way to summarize it in a couple of words. Recommended for the patient.

Perhaps even more impressive than the Riwo Sangchod is Chagdud Gonpa Foundations’s Unsurpassable Healing Incense, one of the few Nepali incenses that actually approaches the level of some of the better Tibetan incenses. Thanks to the categories here I found that this was also in Anne’s Top 10 in 2011! It has a similar ingredient profile to the Riwo Sangchod, with juniper, white and red sandalwood, saffron, valerian, magnolia, musk, aloeswood, myrobalan, olive, jasmine, clove, rhododendron, powdered seashell, frankincense, licorice, cuttlefish bone, wild ginger, betel nut, and powdered alabaster, but even though there are some similarities to the berry/woody mix of that incense, the ingredients add up to something a lot more complex. The first thing I get is some top layer of peppery spice. Second the middle with the woods and saffron. There’s definitely some musk in the mix which is almost entirely absent or at least not noticeably present in most Nepali incenses. As the smoke spreads out more of the incense’s floral notes come out a bit more as well as what seems like a bit of an agarwood note. It only remains noticeably Nepalese by the base which, despite all the other ingredients, still seems a bit (too?) high in juniper or some other cheap sawdust content. Also present are some of the notes found in the Riwo Sangchod as if the incense fractalizes at times. Ultimately there is really a lot going on this one and it can be intensely fascinating to realize that it might take some time to see it at as recognizable rather than ever-changing. In fact I really liked Anne’s description of this as an “all rounder,” it’s almost the perfect way to summarize it in a couple of words. Recommended for the patient.

You must be logged in to post a comment.